South Asians for Human Rights (SAHR), a regional network of human rights defenders, conducted a fact finding mission from 6-10 January 2025 to investigate the compensation process for persons affected by the 2022 climate-induced floods in the Sindh Province.

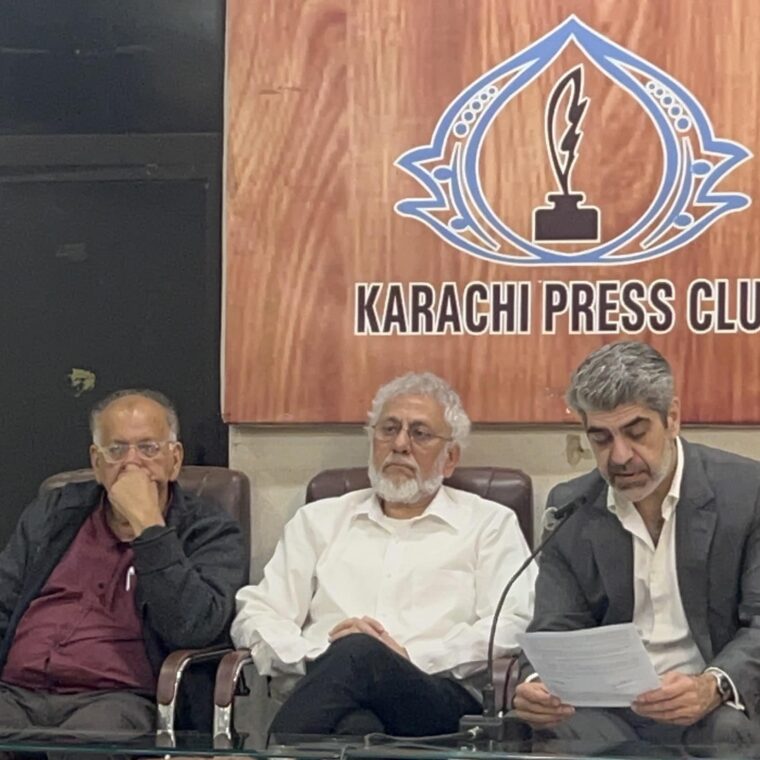

The mission included Ahmad Rafay Alam, environmental rights lawyer and SAHR Bureau Member, Mohamad Tahseen, Executive Director of South Asia Partnership Pakistan (SAPPK) and former SAHR Bureau Member, Farooq Tariq, General Secretary of the Pakistan Kissan Rabita Committee and long-standing SAHR member, and Shahnaz Sheedi of SAPPK. The mission was facilitated by SAPPK.

SAHR conducted a fact finding mission in Larkana, Shikarpur, Nawabshah and Hyderabad districts of Sindh to assess the impact of the compensation and rehabilitation processes conducted after the 2022 climate-induced floods in the province. The mission’s objective was to review the actions and omissions of the government’s performance in the post-flood reconstruction and rehabilitation process as well as document rights violations that have taken place in relation to it.

The mission highlights the following critical concerns:

Inadequate Housing and Infrastructure

The preliminary findings contradict the provincial government’s claims of launching one of the world’s largest housing projects in history for flood affectees. The mission is concerned that the proposed one-roomed ‘flood resilient’ housing model, without basic amenities like a kitchen and a toilet, cannot be acceptable as a home. Further, the mission believes the amount of PKR 300,000 initially provided to build this one-roomed house was insufficient at that time despite the government of Sindh maintaining controlled prices on building material, and at present especially with the sky rocketed inflation rates this amount has become unreasonably low.

The mission doubts the capacity of the flood affected beneficiaries to spend their own funds on building a house without being in debt. The cost of material and labor have drastically risen since the floods, as Pakistan witnessed an all-time high inflation that made cost of living unbearable for the poorest of the poor who are the majority of the affectees.

During the observation tour the mission perceived that the affected communities have been deprived of the comprehensive loss and damage facilitation of basic rights and entitlements of clean drinking water, nutritious food, electricity, education and health care.

Sanitation and Health Crisis

The villages where the mission visited did not have proper sanitation or drainage systems. People have holes in the ground in their compounds to dispose all the excrement and waste. These unhygienic conditions have caused diarrhea, malaria and skin diseases to spread in the community.

Climate Vulnerability and State Responsibility

The mission perceives that these one–roomed houses are not climate resilient at all. As climate change related disaster forecasts suggests, more severe natural calamities will impact this vulnerable population in the future and it is highly unlikely that these structures can withstand another heavy rain. While it is the State’s responsibility to provide shelter, food, education, health and a clean environment to people, these fundamental rights of the vulnerable population have been violated and they are forced to live in inhumane and undignified conditions.

The mission has learnt that that there is very little consultation in the planning process of designing appropriate houses and in the distribution of houses to the genuinely affected communities. The government’s attitude in treating the post-flood reconstruction and rehabilitation process as a ‘routine public service activity’ has diluted the sense of immediacy regarding timely distribution of funds.

Case Study: Village Dhand

In the village Dhand near Moen Jo Daro in Larkana district, 40 houses were destroyed and only four have been built so far. It was informed to the mission that the people have difficulties finding their names on the list of beneficiaries made by the government. Some families still live in tents and some in neighbours’ houses. Those who established houses after the floods are not included in the government list. With an average family consisting of 6 people, it is impossible to live in these single rooms, especially when some family members are married.

Access to Healthcare and Other Related Issues

The mission found women and children bearing a disproportionate burden of the flood’s aftermath. They are suffering from severe malnutrition, with limited access to proper healthcare due to destroyed road networks. The mission observed children attending schools barefoot and without basic supplies, while many girls have been forced to drop out entirely. The floods destroyed road networks, making it difficult for the population to reach hospitals. No attention has been paid to the mental health of the affectees and in some villages, people have become mentally ill due to the suffering.

Agricultural and Economic Impact

The floods also washed away means of subsistence. Some people used to own small amounts of land and others would work on fields owned by waderas (feudal lords). In some cases, the waderas let these people build houses on their land. Climate change effects have made the land difficult to grow crops on and crop yields have reduced to less than half. In Shikarpur and Nawabshah districts, lands are affected by water-logging and salinity. The government subsidies that were provided earlier are insufficient today due to the inflation and the people are finding it difficult to feed their families.

Climate Change Awareness

Awareness of climate change is almost non-existent among the communities and the people the mission interviewed did not have even the basic idea of climate change and its effects. The affected people believe that disasters happened due to their own faults from a religious perspective.

Systematic Failures

The lack of a systematic and holistic framework of compulsory checks and balances entailing regular monitoring and evaluation of the post-flood reconstruction and rehabilitation has paved way to undue delays in rehabilitation and sluggish progress in reconstruction. Political and other reasons have caused fragmentation in the peoples’ voice in advocating for expedited post-flood reconstruction and rehabilitation. Recommendations from local activists and organisations committed to advocating for a comprehensive integrated development process for the affected communities appear to be overlooked by the relevant government authorities.

Climate Finance and Economic Burden

The mission notes that though Pakistan’s contribution to greenhouse emissions is less than one percent, the burden it bears is unjustifiable and the climate finance mechanism is problematic. Sindh has only received approximately USD 2 billion from the World Bank and other financial institutions mostly through debt financing, which in turn needs to be returned with interest, which will come from poor Pakistanis through unjustifiable taxes and add to their miseries. Already a large population in Pakistan lives below the poverty line and the country’s economic situation is poor.

USD40 Billion Flood Bill: No Relief in Sight

The catastrophic floods in Sindh underscore the critical importance of the Loss and Damage fund established at COP27. While the region contributes minimally to global emissions, it bears disproportionate climate impacts, with damages from the 2022 floods estimated at over USD 40 billion. The current financing model, which relies heavily on loans from institutions like the World Bank, forces affected communities to take on additional debt burden for recovery. This creates a cycle of economic vulnerability, as seen in Sindh where flood victims must repay loans with interest through increased taxes, despite already struggling with poverty and inflation. The Loss and Damage fund could provide a more equitable financing mechanism, offering direct support to communities like those in Sindh without adding to their debt burden. However, the fund’s current status – with limited contributions from developed nations and unclear distribution mechanisms – means that immediate relief for regions like Sindh remains inadequate. This gap between climate justice principles and practical implementation continues to leave vulnerable communities bearing both the physical and financial costs of climate disasters.

The mission report detailing these findings and specific recommendations will be released in the coming weeks.

Preliminary Recommendations:

Therefore in this context the Mission calls on the government to:

- review its design of houses and ensure provision of toilets, sanitation and kitchens are included

- review the amount of compensation paid to construct houses in light of present costs of construction

- conduct fresh surveys of affected people to determine whether genuine affectees have been omitted from consideration

In addition, the Mission further recommends:

- Global North countries, responsible for the vast majority of greenhouse gas emissions, should fulfill their promises and commitments of providing climate finance and loss and damage funding to countries bearing the brunt of the climate crisis. Such financing and funding must not be in the form of loans.

- Loss and damage facilities should have robust verification and review processes to ensure funding is received by the people and communities affected by the climate crisis.

On behalf of the mission members,

Rafay Alam,

Bureau Member

Mohammed Tahseen,

Executive Director, SAPPK

About South Asians for Human Rights (SAHR)

SAHR is a regional network of human rights defenders established in 2000 by the late I. K. Gujral, former Prime Minister of India, together with several like-minded South Asian activists including late Asma Jahangir from Pakistan, Dr. Kamal Hossain from Bangladesh, Dr. Devendra Raj Pandey from Nepal and late Dr. Neelan Thiruchelvam and Dr. Radhika Coomaraswamy from Sri Lanka. The purpose of SAHR is to address common human rights violations and challenges to democratic values in South Asia at the regional level.

The current Chairperson of SAHR is Dr. Radhika Coomaraswamy and Dr. Roshmi Goswami is the Co-Chairperson. Ahmad Rafay Alam and Munizae Jahangir are the Bureau Members from Pakistan.